|

| Existentialism in theater |

|

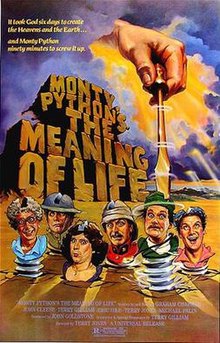

| Existentialism in cinema |

|

| Existentialism in art |

|

| Existentialism in psychology |

From philosophy to psychology

With existentialism becoming a cultural movement and existentialists at the time treated like celebrities, influences of existentialism swept across different disciplines from literature to art, from theater to films, from philosophy to psychology...

Inspired by writings of early existentialists, psychoanalysts and psychologists from Europe began applying existentialist principles to the practice of psychotherapy in the 20th century. The fusion of existentialist philosophy with psychology first crystallized in the work of Otto Rank (1884-1939), an Austrian psychoanalyst who was one of Freud's closest associates until he criticized Freud for reducing all emotional experiences to sex... Influenced by Nietzsche, Rank saw the denial of emotional life as denial of the will (the creative life) and the interpersonal relationship in the analytic situation so he took a 180-degree turn from classical psychoanalysis and made the relational and experiential aspects of the "here-and-now" central to his practice of psychotherapy. Not only was Rank quite possibly the first existential therapist, he was also the first to coin the term "here-and-now" and recognized its importance. In Will Therapy (1929-31), Rank wrote:

|

| Otto Rank |

"The neurotic lives too much in the past to that extent he actually does not live. He suffers... because he clings to, wants to clings to it, in order to protect himself from experience, the emotional surrender to the present" (p.27)

Unfortunately, Rank's work remained largely unrecognized until much later. Unaware of Rank's writings at the time, Swiss psychiatrist, Ludwig Binswanger (1881-1966) began combining psychotherapy with existential and phenomenological ideas in his work with patients at the Kreuzlingen sanatorium. Influenced by Husserl, Heidegger, and Sartre, Binswanger expounded his concept of existential analysis as an empirical science that involves an anthropological approach to the individual character of being human in his book, Basic Forms and the Realization of Human "Being-in-the-World" (1942). Around the same time, an important figure in existential psychology was suffering in one of the Nazi concentration camps, wrestling with the meaning of life. It was Victor Frankl (1905-1997), an Austrian Jewish neurologist and psychiatrist. Fortunately, Frankl survived the Holocaust and after being liberated in 1945, wrote his world-famous book, Man's Search for Meaning (1959), detailing the events inside the concentration camps that shaped his beliefs, at the same time, introducing logotherapy, an existential therapy focusing on Kierkegaard's will to meaning.

While existential psychology was being introduced in various parts of Europe, it and its main thinkers - including Ludwig Binswanger, Melard Boss, and Victor Frankl - "were almost entirely unknown to the American psychotherapeutic community" (Yalom, 1980, p. 17)! This was not surprising as existentialism was only being quietly introduced in university classrooms in the 1930s. Even Rollo May (1909-1994), an early contributor to existential psychology in the U.S., was only introduced to existentialism through Paul Tillich at the Union Theological Seminary after Tillich had immigrated to the U.S. in 1933 (Wright, 1974). After being introduced to existentialism, May, through his work such as Existence (1958) and Love and Will (1969), played an important role in introducing existential psychology and keeping the existential influence alive in America. During this time, much of Ludwig Binswanger's had also been translated into English, helping to popularize existential ideas as a basis for therapy (Cooper, 2003).

Yet it was not until September 5, 1959 when Rollo May, Abraham Maslow, and Herman Feifel participated in the American Psychological Association (APA) Symposium on Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy existential psychology began to reach the forefront of psychological thought and practice. By the 1960s, existentialism had become the "buzz" of psychology! Since then, there have been a number of prominent figures in existential psychology and psychotherapy including James Bugental, Irvin Yalom, Kirk Schneider, Stephen Diamond, etc...

References

Cooper, M. (2003). Existential therapies. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications.

Wright, E. (1974, May). Paul Tillich as hero: An interview with Rollo May. Christian Century, 530-533.

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books Publishers Inc.

Upcoming...While existential psychology was being introduced in various parts of Europe, it and its main thinkers - including Ludwig Binswanger, Melard Boss, and Victor Frankl - "were almost entirely unknown to the American psychotherapeutic community" (Yalom, 1980, p. 17)! This was not surprising as existentialism was only being quietly introduced in university classrooms in the 1930s. Even Rollo May (1909-1994), an early contributor to existential psychology in the U.S., was only introduced to existentialism through Paul Tillich at the Union Theological Seminary after Tillich had immigrated to the U.S. in 1933 (Wright, 1974). After being introduced to existentialism, May, through his work such as Existence (1958) and Love and Will (1969), played an important role in introducing existential psychology and keeping the existential influence alive in America. During this time, much of Ludwig Binswanger's had also been translated into English, helping to popularize existential ideas as a basis for therapy (Cooper, 2003).

Yet it was not until September 5, 1959 when Rollo May, Abraham Maslow, and Herman Feifel participated in the American Psychological Association (APA) Symposium on Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy existential psychology began to reach the forefront of psychological thought and practice. By the 1960s, existentialism had become the "buzz" of psychology! Since then, there have been a number of prominent figures in existential psychology and psychotherapy including James Bugental, Irvin Yalom, Kirk Schneider, Stephen Diamond, etc...

References

Cooper, M. (2003). Existential therapies. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications.

Wright, E. (1974, May). Paul Tillich as hero: An interview with Rollo May. Christian Century, 530-533.

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books Publishers Inc.

Next let's talk more about meaning...